When talking with the average person about environmental issues, one is regularly met with the assertion that the underlying problem is ‘just too many people’. There’s an intuitive logic to this position. The global human population now stands at over 8 billion, having exploded from fewer than 1 billion in 1800.

There’s no question that this brings environmental impacts. A recent study estimated that humans now comprise over 35 per cent of the total mammalian biomass on the planet; an incredible proportion for a single species. However, contrary to common perceptions, the human population isn’t growing exponentially – it stopped doing this in the early 1960s. The UN expects a population peak just past the middle of this century, at around 10 billion.

Excessive consumption

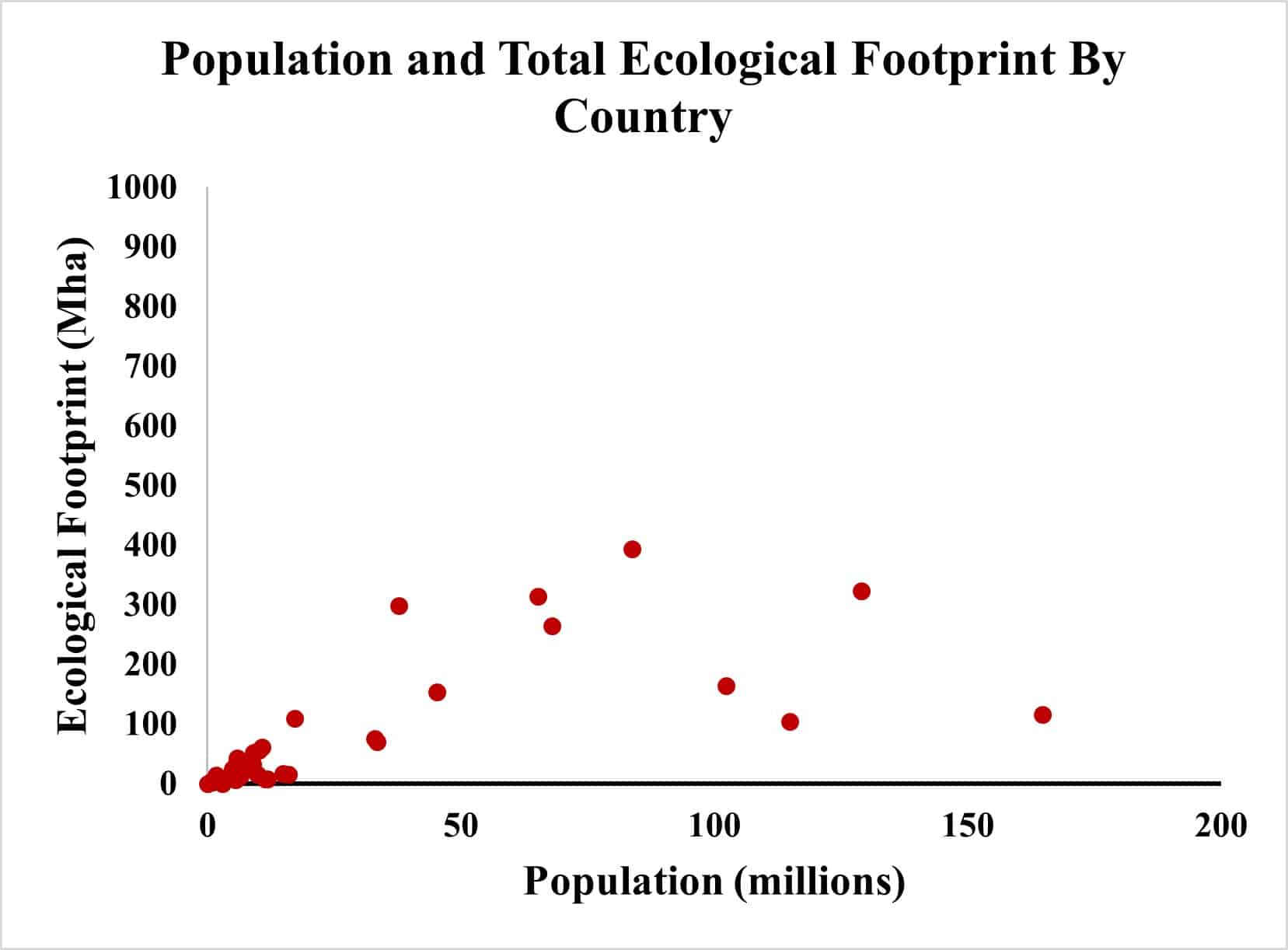

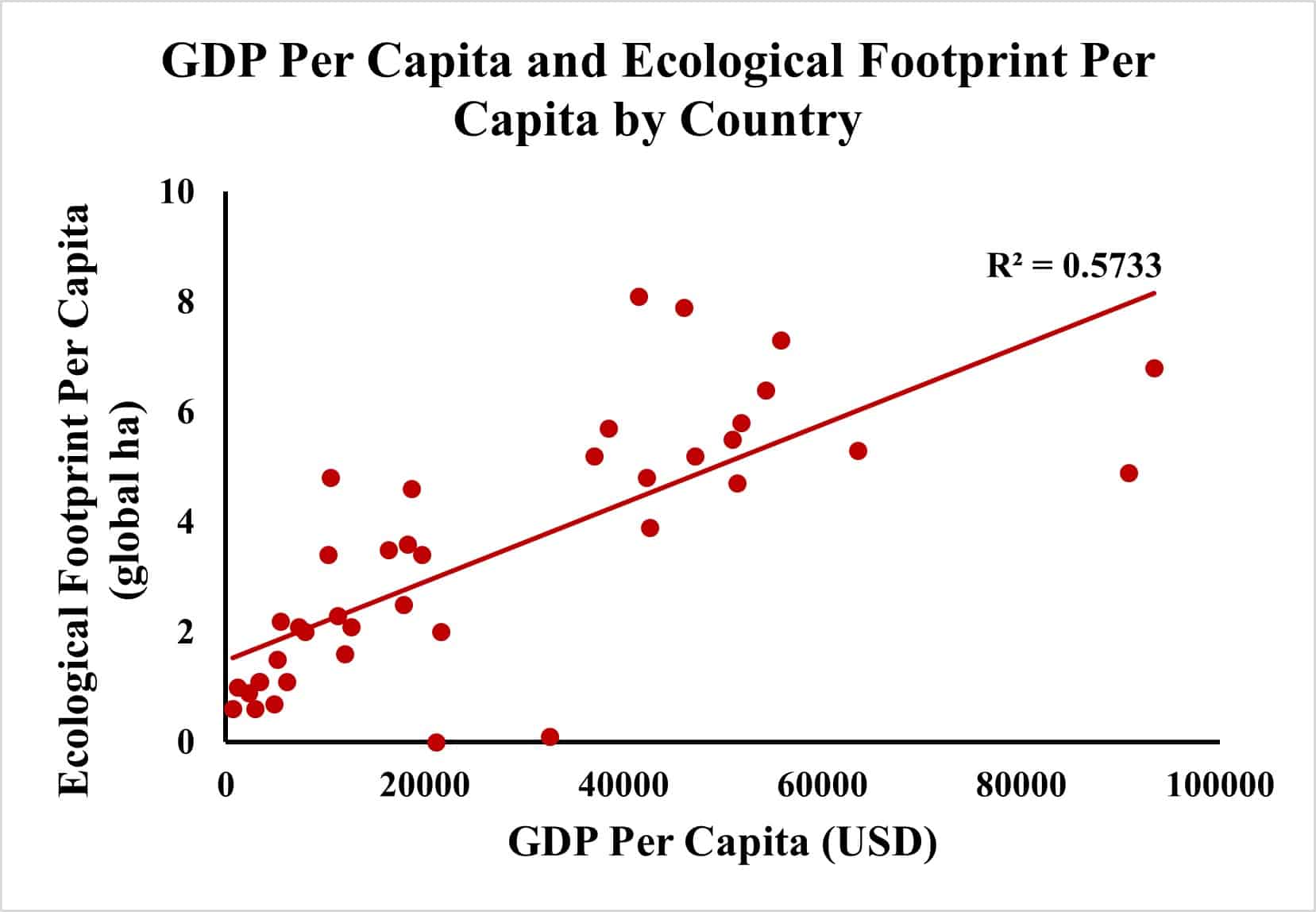

The idea that population is in itself the major driving force behind environmental destruction is misleading, as it rests on the implicit assumption that all people have equal environmental impacts. This could hardly be further from the truth. Both within and between countries, high greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and ecological destruction are not driven by people in general, but by the richest consumers with the most resource intensive lifestyles. Therefore, a far more urgent threat is excessive consumption, and the economic systems that underpin it.

Road traffic, responsible for a sizeable proportion (10-15 per cent) of anthropogenic emissions, is a multifaceted problem of wealth, lifestyle, urban planning and motor industry marketing – not so much the number of people. Again, both within and between countries, the more affluent generally have higher rates of car ownership, while poorer strata rely more heavily on active or public transport. This disproportion is especially stark in the trend for SUVs, an environmental scourge overwhelmingly driven by the wealthy, and whose drivers collectively have higher carbon emissions than most countries.

The livestock population, contributing an even larger share of emissions, is growing at almost double the rate of the human population, as ‘western’ diets heavy in meat and dairy gain popularity in emerging economies. While people make up over a third of mammalian biomass, domestic livestock make up almost 60 per cent.

China

Growing demand for the beef and soy fuelling the destruction of the Amazon and Cerrado ecosystems comes not from countries with highest population growth, but from the large consumer economies of China and western Europe, where population growth has plateaued. China does of course have a large population of 1.43 billion people, but demographers suggest that this will peak in the next several years if it hasn’t already – besides which, China has far larger GHG and ecological impacts than India, despite a comparable population.

Fig. 1: National population plotted against national ecological footprint in millions of hectares.

Fig. 2: GDP per capita plotted against ecological footprint per capita in hectares. Each data point is a country from 40 chosen at random.

This misplaced emphasis on ‘overpopulation’ can lead to ugly consequences. The modern iteration of the population panic can be partly traced to a hysterical and largely discredited 1968 book by evolutionary biologist Dr. Paul Ehrlich, The Population Bomb, which reheated the theories of Thomas Malthus to argue that population growth was pressing against environmental limits, and would bring devastating consequences within decades. In the opening of the book Ehrlich recounts a cab ride during a trip to Delhi, which awakened him to the issue. He paints a picture of crowded squalor, with ‘people defecating and urinating. People clinging to buses. People herding animals. People, people, people, people’ – evoking imagery reminiscent of swarming insects to induce discomfort at the very idea of such a throng.

Overpopulation panic

There’s a problem with this picture. At the time that Ehrlich wrote with such disdain about Delhi, the population of that city was just over 2.8 million. Meanwhile, the population of glitzy Los Angeles was 7.4m, Paris was home to 7.9m and New York city boasted 15.2m inhabitants. You can form your own conclusions about why it was in India’s capital rather than any of these other cities that Ehrlich saw a problem, but the overpopulation panic became a useful dog whistle within a long history of environmental language covering for racism.

This concern about population begs the question: what solutions do its adherents propose? Ehrlich advocated not only the provision of contraception and family planning to the third world, but also sterilisation campaigns. The Indian government under Indira Gandhi subsequently took this idea to the extreme when, strongly encouraged by the United States, it began a mass sterilisation programme initially coercing poor men into vasectomies, later shifting the focus to women. In 1976 alone, 6.2 million men were sterilised – about 15 times more people than were sterilised by the Nazi eugenics campaign.

In China, the infamous one-child policy begun in 1979 was undoubtedly effective at slowing population growth, but resulted in decades of forced and botched abortions and the widespread abandonment of baby girls (seen as culturally inferior to boys). Moreover, it made no noticeable dent in China’s emissions growth.

Flawed conceptions

Most people will be horrified by these coercive human rights abuses, but many argue that voluntary means of population reduction are environmentally necessary nevertheless. Even if we were to accept that argument in principle, family planning and demographic transition would be unlikely to reduce population on a timescale that mattered for averting catastrophic climate and ecological breakdown.

Of course, access to family planning, contraception and safe abortion are important for other reasons, but unless they were targeted at millionaires and billionaires, should hardly be seen as an environmental intervention; moreover, those in wealthy nations should be wary of the neocolonial undertones of imposing them on the developing world under flawed conceptions of development aid.

The ‘overpopulation’ myth allows affluent people in developed countries to absolve themselves of responsibility for effecting fundamental change to the global economy and their own consumption, and instead to heap blame on those who have contributed least to our environmental predicament. The global racialised poor, especially women, pay the price twice over, finding themselves at the sharp end of both the environmental crisis, and of the rich world’s self-abrogating and patronising ‘solutions’.

Related: Sunak warns ‘no alternative’ to curbing inflation as he defends rates hike