PM Boris Johnson made a promise in July to increase the UK’s Covid-19 testing capacity to 500,000 tests per day by the end of October.

The latest data on the Government’s coronavirus dashboard shows that there is currently a capacity for 467,512 tests with 308,763 tests actually being processed.

The Prime Minister may not be far off his target with just one day left to meet it – but will it be a huge success that will help make a real difference to the current escalating problem of rising infection numbers?

Dr Joshua Moon, research fellow in the Science Policy Research Unit (SPRU), University of Sussex Business School, said the Government will “probably” reach the target.

Limited

“But what that tells us is limited,” he said. “The gap between capacity and tests done is important here because the capacity figure generally refers to overall testing capacity, not the Pillar 1 & Pillar 2 testing capacity which are linked to Test and Trace.”

Dr Moon said testing capacity alone is “not the route to suppressing the virus”, adding: “We need a contact tracing system that can handle the number of cases referred to it, we need better support and enablers for isolation, and a Government communications strategy that is engaging, multi-media, and consistent.”

Dr Bharat Pankhania, senior clinical lecturer at the University of Exeter Medical School, pointed out the importance of a quick turnaround regardless of testing capacity.

Just 22.6% of people who were tested for Covid-19 in England in the week ending October 21 at a regional site, local site or mobile testing unit – a so-called “in-person” test – received their result within 24 hours.

Dr Pankhania said it is key for the system to be “dynamic and responsive”, locally delivered and locally based with people not having to travel long distances.

“If you have local commanders in place, the local commanders can determine, as gatekeepers, who needs to be tested and it actually keeps your capacity operating at an optimal level,” he said.

Dr Pankhania also talked of the importance of targeting the testing where it is most needed – to people in nursing homes, hospitals, healthcare workers, emergency workers – so that they can get tested regularly.

“What you need to do is use the capacity in a smart manner,” he said.

Professor Jonathan Ball, professor of molecular virology, University of Nottingham, said testing is “only one part of the jigsaw”.

He said: “It’s how it informs infection control that’s key, whether that’s through influencing the behaviour of the person receiving a positive test result and their immediate household, or effective and rapid contact tracing that should also follow a positive result.

Missing

“One thing missing from testing policy is how we might deploy increased capacity for better surveillance – especially in hospital, care home, prison, and educational settings – and how we might be able to use testing to manage contacts: asking people to repeatedly isolate when they might not be infected is far from ideal.”

This is not the first target the Government has set itself regarding testing since the pandemic began.

On April 2, after several days of intense scrutiny over failures in testing, Health Secretary Matt Hancock set a target of achieving 100,000 daily coronavirus tests in England by the end of April.

At this time, only about 10,000 tests were being carried out each day, but Mr Hancock remained confident that the target would be met.

Some 80,000 were carried out on April 29 – but it jumped by 40,000 in the final 24 hours to just over 120,000.

The Government said it met its target, with Mr Hancock heralding this as an “incredible achievement”.

He said 122,347 tests were performed in the 24 hours to 9am on Friday May 1.

But questions were raised over how the tests were counted, with changes in the last few days meaning newer home test kits were counted as they were sent out.

The overall total also included tests dispatched to “satellite testing locations” – such as hospitals that had a particularly urgent need – but did not detail whether the tests were actually used.

It meant the number of tests known to have been carried out in the 24 hours, as opposed to delivered, was 81,978.

Whether the Prime Minister will meet his 500,000 testing capacity target remains to be seen, but with the end of October just hours away time is running out.

Rise in England

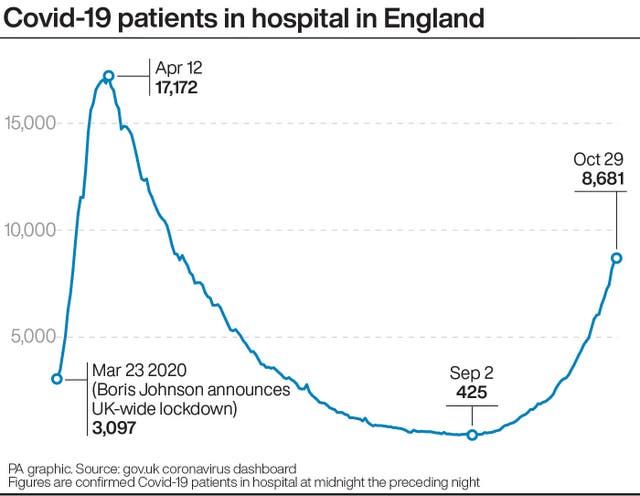

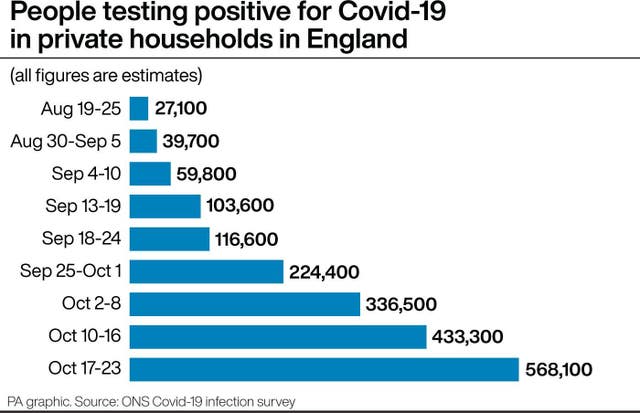

Cases of coronavirus in England have jumped 47% in one week, according to new data.

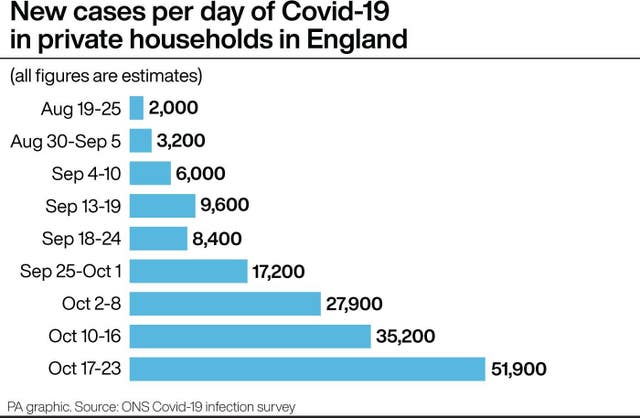

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) infection survey found cases “continued to rise steeply”, with an average of 51,900 new cases per day of Covid-19 in private homes between October 17 and 23.

This is up 47% from 35,200 new cases per day for the period from October 10 to 16, according to the ONS estimates.

Overall, around one in 100 people had Covid-19 over the course of the latest week.

In September, the Government’s chief scientific adviser, Sir Patrick Vallance, warned that, without action, the UK could see 50,000 coronavirus cases a day by mid-October.

He announced his stark projection at a press conference alongside chief medical officer Professor Chris Whitty, adding that there could be 200-plus daily deaths.

The ONS figures, based on 609,777 swab tests taken whether people have symptoms or not, do not include anyone staying in hospitals, care homes or other institutional settings

Highest rates

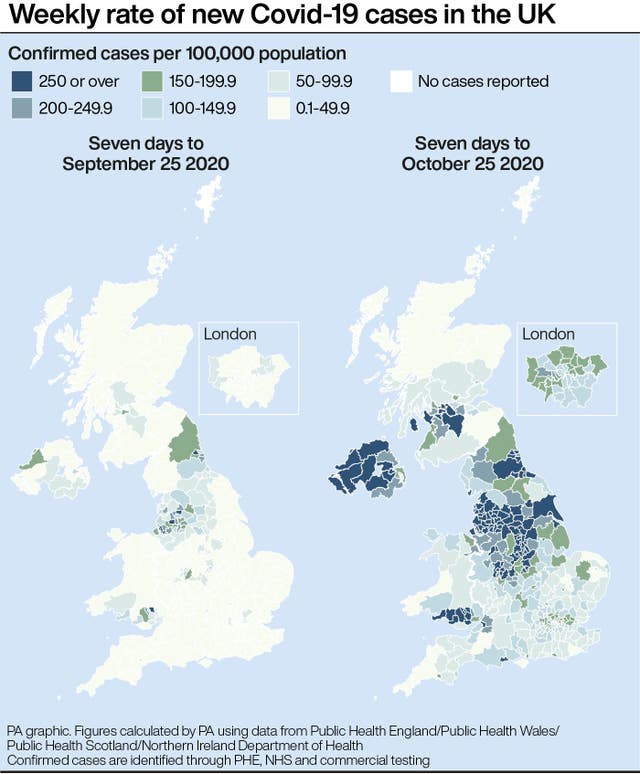

The highest rates are in the North West and Yorkshire and the Humber, the data showed.

Rates also remain high in the North East, but the ONS said these have now levelled off and “there is now a larger gap with the other two northern regions”.

Analysis by the PA news agency of the data shows that the estimated percentage of people in north-east England testing positive went from 0.57% for the period September 12 to 25 to 1.41% for the period of September 26 to October 9.

But the rate of increase appears to be levelling off, with the latest figure being 1.43% for the period October 10 to 23.

In contrast, the North West has jumped from 1.57% for September 26 to October 9 to 2.47% for the period October 10 to 23.

The lowest rates are in the South East, South West and eastern England, while there has been growth in all age groups over the past two weeks.

Katherine Kent, co-head of analysis for the Covid-19 infection survey, said: “Following the expansion of ONS infection survey, we are now seeing evidence of increases in Covid-19 infections across the UK.

“In England, infections have continued to rise steeply, with increases in all regions apart from in the North East, where infections appear to have now levelled off.

“Wales and Northern Ireland have also all seen increased infections, though it is currently too early to see a certain trend in Scotland, where we have been testing for a shorter period.

“When looking at infections across different age groups, rates now seem to be steeply increasing among secondary school children whilst older teenagers and young adults continue to have the highest levels of infection.”

R value

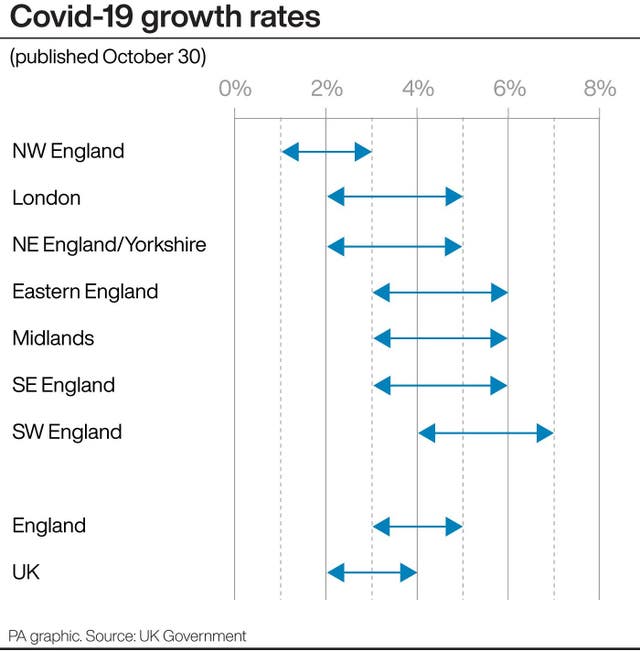

It comes as the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (Sage), which advises the Government, said the reproduction number, or R value, of coronavirus transmission for the whole of the UK has nudged down to between 1.1 and 1.3 – representing the situation over the last few weeks.

Last week, the group said the R number was between 1.2 and 1.4.

A major study earlier this week suggested 100,000 people are catching coronavirus every day in England, double the number suggested by the ONS.

The React study, by Imperial College London, found the pace of the epidemic is accelerating and it estimated the number of people infected is now doubling every nine days.

The authors argued the country is at a “critical stage” and said “something has to change”.

Separate figures from the Zoe app study run by King’s College London suggests the number of daily new Covid-19 cases in the UK is continuing to steadily increase, but is not surging.

Researchers there said there are currently 43,569 daily new symptomatic cases of Covid in the UK on average over the two weeks up to October 25 (excluding care homes).

Related: Study suggests Eat Out To Help Out is responsible for “significant” rise in infection rates