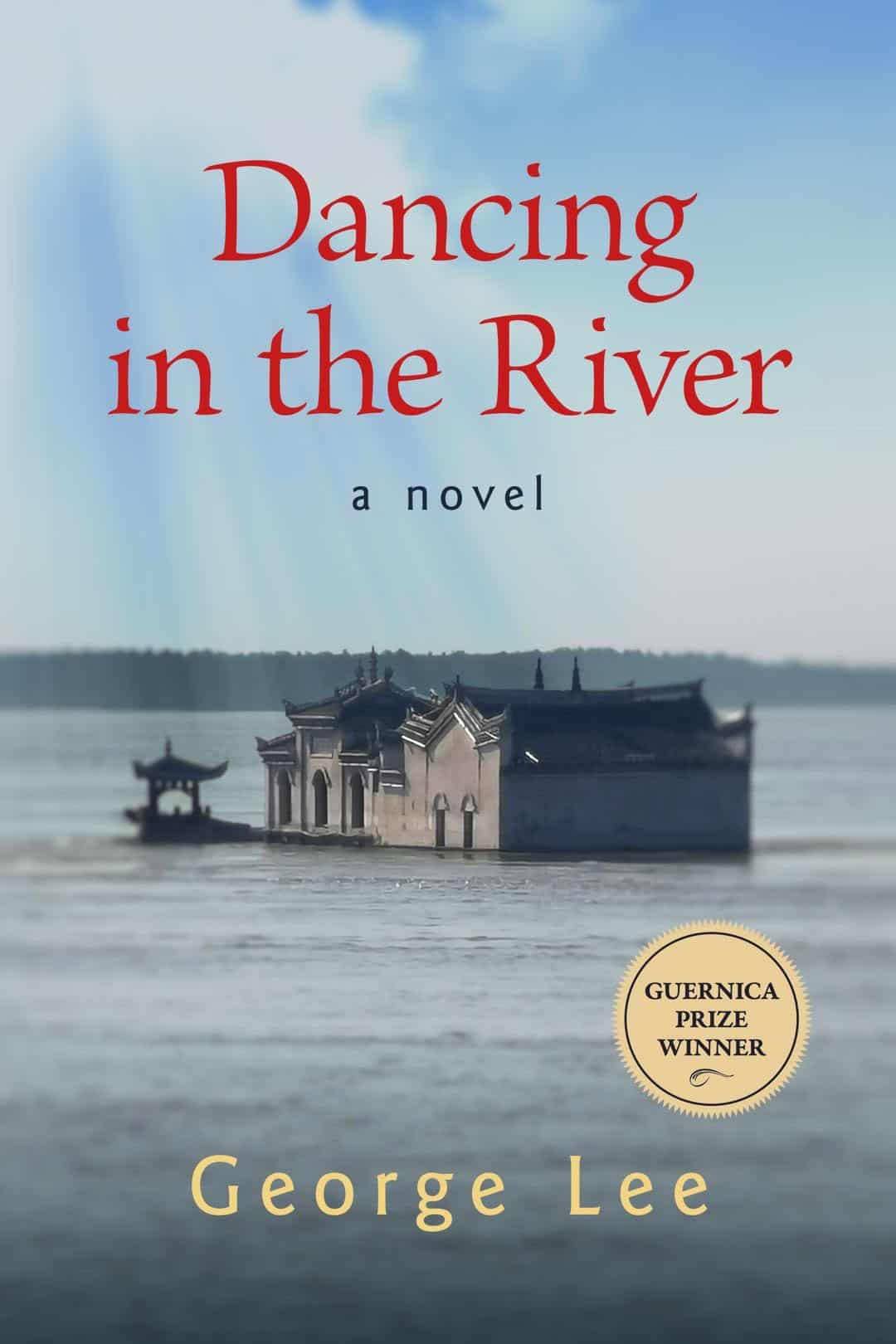

The year 2022 marked the arrival of a stunning new voice in literary fiction, whose debut novel –Dancing in the River – retold in fictional form the author’s traumatic experiences growing up amidst the chaos and fear of China’s Cultural Revolution.

In 2021, the original manuscript won the prestigious Guernica Prize for Literary Fiction in author George Lee’s adopted home, Canada, and the praise for its poetic yet powerful analysis of oppression on the body, soul and mind of the individuals has only increased from there.

The Chinese-Canadian writer, 60, says that one of the grand purposes of penning the acclaimed novel is to build a bridge between today’s China and the West.

When asked about how the book will help close the divide between these two cultures – a pressing concern in a time of rising political polarization – he does not answer directly but, instead, cites an anecdote concerning Albert Einstein, whose name is now arguably as associated with the peace cause as it is with science.

“One day, Dr. Einstein’s teaching assistant was about to distribute final exam papers to a physics class,” he says.

“Suddenly, he realised something had gone wrong. So, he rushed back to Dr. Einstein’s office as quickly as possible. ‘Professor,’ the sweating young man was gasping for air, ‘did you give me the wrong exam papers?’

“’No,’ replied Einstein.

“But the questions are the same as those the year before!

“Slowly, Einstein looked up from his reading glasses and said, ‘Yes, but the answers are different this year.’”.

Making his points through anecdotes and parables is one of Lee’s signature storytelling devices, utilised to great effect throughout Dancing in the River.

He explains that he learned this subtle yet striking approach from reading the New Testament, a book that was for many years forbidden to him and all Chinese citizens while under the yoke of Chairman Mao.

“Speaking in parables can directly communicate with the reader’s subconscious mind,” he adds, revealing the importance he puts on the deeper, connected core of humanity, beneath the layers of mental conditioning that individual societies impose upon their people.

If you have ever wondered how crushing life would be like in a culture that is determined to exterminate free thinking and belief in favour of a strict, anti-Capitalist code, then Dancing in the River provides the answers.

The engrossing coming-of-age story reflects Lee’s upbringing in China, from the infamous Cultural Revolution to the post-Mao reform following his death in 1976.

Divided into three sections, the novel closes in 1989 when the Tiananmen Massacre occurred, and the protagonist, Little Bright, decides to flee the communist regime, relocating to Canada, where he still lives today and works as an attorney, family mediator, and life coach.

Raised during the Cultural Revolution, Lee described it in his novel as an upbringing of “ideological indoctrination and brainwashing” that aimed to degrade his generation to the edge of an animal-like existence.

Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Mao Zedong was, he says, “worshipped as a god”.

“Obeying him and his party was the highest order of the day. Any doubtful thoughts or slightest aberration would bring disaster.

“Knowledge was deemed as poisonous and Western countries as evil.”

When Mao died in 1976, however, China opened its doors to the West, and Lee and his peers were suddenly encouraged to learn the once-forbidden English language.

There was, however, a hidden agenda for the Communist Party. As one of the party representatives in Dancing in the River puts it:

China has a unique culture with a history that is five thousand years old. We learn from foreigners only to conquer them. We will never forget how the eight allied forces burned down the Summer Palace and how the foreigners humiliated us by enforcing unfair treaties against our will and weakened the sovereignty of our nation.

“Chinese people harbour irascible memories,” continues Lee. “If revenge is on the agenda, they can patiently wait 100 years for an opportunity.

“For example, the disgrace and hurts inflicted by the Opium Wars on the psyche of the Chinese people are as lividly felt as 183 years ago. Such a distinct character is in the Chinese gene.”

The difference between the collective mindsets of China and the West is made clear in Lee’s novel, such as in the following passage, where Little Bright discusses the matter with some school friends.

I still remembered the night when we ate frogs at Big Guy’s house after labour class. But I lost my appetite. “No, no. I eat eggs and tofu,” I replied.

“If we drink milk every day, do we grow white, like white guys?” Bubble asked jokingly.

“Confucius said all humans are the same, despite differences in habits,” Red said.

“How come Chinese are so different from Americans, then?” Big Guy asked.

“Because we find pleasure in our stomachs, they find their happiness in their dreams,” I said. “We have no stomach for their hot dogs, and they have no stomach for hearts that once belonged to pigs. We eat different foods; we think different thoughts.”

“Americans eat dogs too?” Red asked.

“They eat man-made dogs, fake ones, silly,” Bubble declared.

“In terms of thinking, I learned that Westerners use the left hemisphere; they call it intellectual thinking. We often use right hemispheric thinking, known as intuitive thinking,” I said, unable to resist showing off my knowledge.

“Too complicated.” Big Guy shook his head.

Lee experienced the tension between the two ways of thinking early on in his life.

At college, and now living in the post-Mao era, he discovered the charms of English literature, devouring the works of Shakespeare, Charles Dickens, Victor Hugo and others.

As the novel relates, so enchanted is Little Bright that he renames himself ‘Victor’ (in honour of Hugo, perhaps).

But it was the Sherlock Holmes stories of Sir Author Conan Doyle that made the greatest impression, being the catalyst for an intellectual awakening that caused tension between the strict Chinese moral codes of rights and wrongs and Western systems of inductive and deductive reasoning.

“If the reasoning is the scientific measure to discover truths, then the Chinese moral system must be wrong,” contemplates his protagonist in the novel.

Lee describes the process of intellectual discovery as a “lonely quest” to test and find the truth for himself – a radical departure from the Chinese educational curriculum.

Upon graduating from college, he became a high school teacher of English and experienced first-hand how the Communist Party continued to distort the Western ideology of freedom and democracy in the curriculum.

During this time, the pressures of political conformity were so great that one of his students committed suicide, something that still pains him to think about today.

Tired of being part of the apparatus that curtailed rather than expanded young minds, he decided to quit his teaching position and attend graduate school.

In one of the graduate classes, Lee read the Bible – another previously forbidden text – which he says led him to find “new spiritual truths to complement my intellectual awakening”.

With tensions between his own learnings and enforced ideology only increasing, he ultimately chose to leave his homeland for the West.

In Dancing in the River, in a chapter set during the eve of the Tiananmen Massacre, Little Bright delivers a radical speech calling on college students to seek and uphold freedom:

I looked up at the sky, thinking everything that had happened in my life had spurred me to dive deeper than the surface of life into an uncharted dimension. Now, I had stepped out of the bondage of mind and emotion and awakened to the truth within me.

In Canada, Lee achieved a master’s degree in English literature, followed by law school.

However, he says he had always harboured a desire to become an author.

“I always wanted to be a writer, and the publication of Dancing in the River is a dream finally come true,” he declares.

With our interview almost at a close, Lee returns once more to our earlier conversation about building a bridge between the West and China, this time referencing the famous Brothers Grimm fairy tale, The Frog Prince.

“What about the frog, to kiss or to eat?” he asks, smiling.

“The frog is under a wicked spell. You can transform it into a handsome prince with a magic wand.

“The magic wand in today’s world is to understand the Chinese psyche. The only way to win a war is to know yourself and know your enemy, as says Sun Tzu in the Art of War.”

Lee makes clear in his unputdownable novel that the real ‘enemy’ is the political leader who imposes their own negative impulses upon the masses. More often than not, they have no choice but to accede.

And with Dancing in the River, Lee has penetrated the Chinese minds more than any other novels in the genre to remind us of this.

At a time when the barriers pulled down so decisively only three decades ago are once again being rebuilt, his honest and unflinching story is more important than ever.

Dancing in the River by George Lee (Guernica Editions) is out now on Amazon, priced £19.99 in paperback and £7.95 as an eBook.