Look around and everywhere you will see people staring at small screens. Indeed, you may, yourself, be reading this on your smartphone or tablet.

In the space of a decade or so, since Steve Jobs first unveiled the revolutionary iPhone, we have become addicted to these tiny two-way windows on the world, at the expense of actual human contact.

Meanwhile, there has been a clear rise in cosmetic surgery procedures as the ‘selfie’ generation, led by influencers, becomes ever-more desperate to look picture-perfect within their social networks.

It may hard, at first glance, to think that one device could be responsible for these social shifts, but, it turns out, the smartphone is only the latest in a long line of visual inventions and technological innovations that have altered the way we view ourselves, both individuals and as a species.

The act of seeing, and being seen, it turns out, are crucially important to our understanding of who we are and how we got here, though the role of sight in our cultural evolution has never really been documented, until now.

Susan Denham Wade first hit upon the idea that, when it comes to our sense of sight, there may be more than meets the eye in 2015 when #thedress debate exploded across the internet.

This hinged around the question of whether a certain striped dress was black and blue, as some people saw it, or white and gold.

The author, a former media executive, wondered if we can see the same thing differently then does it also follow that those who preceded us likewise viewed the world differently than we do ourselves?

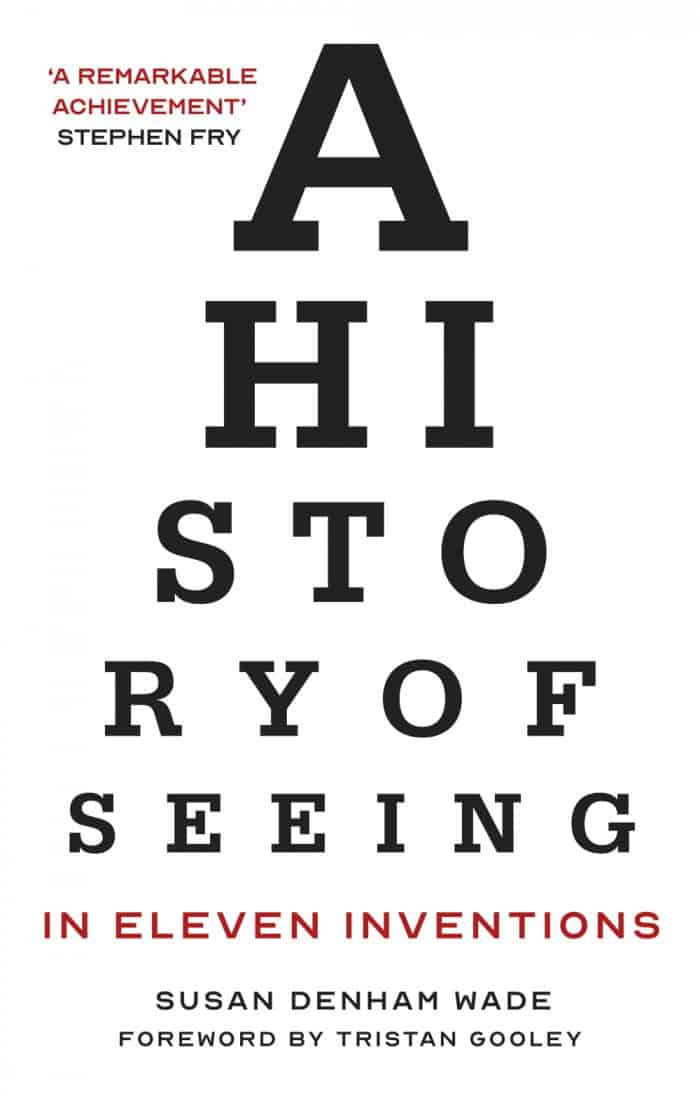

She answers this profound question decisively in her new book, A History of Seeing in Eleven Inventions, which has just been published by Flint Books, an imprint of The History Press.

Heavily researched and packed with fascinating, little-known insights into our past, the book explores the history of seeing from the first emergence of sight in the animal kingdom all the way to our modern preoccupation with all things visual.

As the title suggests, it frames this remarkable story through a focus on 11 visually-related inventions that each have had, in their own way, a significant impact on the development of human behaviour and civilisation.

Broad in scope, the book fundamentally slots into the ‘smart thinking’ genre as popularised by writers such as Yuval Noah Harari, Bill Bryson, Malcolm Gladwell and Steven Johnson. That is, the subject is handled with a rigorously academic approach but translated to the reader in an accessible and enjoyable format.

The fact it also boasts an unusual take on history means it can also draw parallels with Hugh Aldersey-Williams’ Tide, Lucy Worsley’s If Walls Could Talk and Matthew Walker’s Why We Sleep.

The 11 inventions discussed by Denham Wade span more than one million years and the whole globe, from our origins in East Africa and the dawn of civilisation in the Middle East, to the later dominance of Western Europe and, bringing us bang up to date, the USA.

Each invention—making fire, art, mirrors, writing, glasses, the printing press, the telescope, industrialised light, photography, moving images, and the smartphone—is covered in a dedicated chapter, making A History of Seeing in Eleven Inventions the perfect book to dip in and out of.

The narrative, meanwhile, also traverses natural and scientific history, art and psychology, and details experiments, hypotheses, social commentary and popular culture, as it sets out the historical and social ramifications of each invention’s emergence.

With the first invention, for example, Denham Wade discusses how mastery of fire marked humanity’s first break from the dictates of nature, prompting the ongoing journey towards control of our environment.

The appearance of the mirror, meanwhile, around 8,000 years ago in what is now Turkey, coincided with the rise of self-awareness, and a shift from tribal to individual identities, while the arrival of writing made language a visual medium, enabling long-distance communication that, in time, would underpin the transition from customs to laws, villages to empires, and chiefs to kings.

Even more humble inventions have also, surprisingly, consequently led to massive upheavals.

Spectacles, which originate in the 13th century, extended the productive lives of master craftsmen and allowed people to seeing new details that aroused European curiosity and enquiry after centuries of cultural darkness.

Centuries later, industrial light enabled the factory system and the urbanisation of society that defines the Industrial Revolution.

The chapter on the final invention on the list, the smartphone, has the provocative title ‘Seeing, Weaponised’. Here, Denham Wade takes to task our ongoing love affair with the small screen and the wider issue of living in a world where sight is the dominant sense.

From the moment we wake up to when we close our tired eyes, we are being constantly bombarded by the visual, be that advertising and branding competing for our attention, TV, or social media.

Smell, hearing, touch, taste are very much secondary senses, and it’s now more common to watch a loved one on video than actually greet them in person.

This, she warns, may be harming our wellbeing, and she brings numerous scientific studies to support her position, such as a 2016 paper published in the Personality and Social Psychology Review that found that being touched reduces stress levels and promotes relational, psychological, and physical well-being in adults.

Touching a keyboard or smartphone screen doesn’t count.

Similarly, she speculates on whether the modern lack of access to the natural, primal smells our ancestors had—grass, rain, sea, soil, our own bodies, fresh vegetables—could be contributing to the mental health pandemic of today.

Again, research suggests this may be the case. A separate 2016 study found a very strong link between the loss of the sense of smell and depression.

Perhaps, she concludes, the rise of visual inventions means our senses can no longer keep up, and that it’s high time to step back into the real world we’ve been drifting away from ever since we first learned to light up the night.

The book’s postscript discusses the impact that Covid has had on our senses, where some 10 per cent of those infected have been left without the ability to taste or smell. In this ‘new normal’ the small screen has proven a godsend for keeping friends, families and colleagues connected, but will this prove the final blow against our five senses, or will we be able to free ourselves from the slavery of sight?

It is an especially thoughtful ending to a work which is never less than brilliant, and which, importantly, makes the reader feel equally clever.

Full of twist and turns, and packed with unfamiliar aspects of familiar periods or events, this is a history book that is a sight for sore eyes, being entertaining, engaging, and highly original.

A History of Seeing in Eleven Inventions by Susan Denham Wade is published by Flint Books (The History Press) and is out now on Amazon in hardback priced at £20, in paperback priced at £12.99, and as an eBook priced at £2.84.

EXCLUSIVE Q&A INTERVIEW WITH AUTHOR SUSAN DENHAM WADE

A History of Seeing in Eleven Inventions author Susan Denham Wade tells us more about her new book, why sight’s historical role in our development shouldn’t be overlooked, and what she hopes readers will gain from looking at history through another lens.

Q. How did your own poor eyesight, and a certain dress, factor into the genesis of your book?

A. Seeing has always played a central role in my life, given that I have had severe short-sightedness since my childhood. It always struck me that had I been born a few centuries earlier then I would have been blind!

Across my working life I have been heavily involved with visual technologies, at one point working within the BBC to oversee their expansion into digital, multi-channel broadcasting.

So the visual has always held a fascination but it was the internet phenomenon of #thedress in 2015 that really motivated me to investigate the history of seeing, surprisingly a subject that no-one else has seemingly tackled before now. The dispute raging over social media, and even in the media, about the colour of this dress made me consider the question that if two people in the same room can see the same thing yet disagree about it so fundamentally then, perhaps, our ancestors similarly viewed the world in a different way to us.

I spent four years researching this central question, going down many fascinating paths along the way, and the answer was yes, they did, and the visual inventions that have arisen over the centuries have been largely responsible for those shifts in our ways of seeing.

Q. What do you think readers will learn about humanity from a survey of history through the lens of seeing?

A. I hope it will make them think about how profoundly what we see can change how we think and act, and how profoundly the prevailing worldview at a point in time affects every aspect of society, from attitudes to spirituality, politics and science, to the small details of daily life.

Q. Your book details 11 inventions that have been both pivotal to our rise as a species, and to our constant re-evaluation and reinvention. Which one invention would you pick that has most changed our way of looking at, and thinking about, ourselves?

A. Well, that would have to be the mirror! We take mirrors for granted as a convenient tool, but through history they have been deeply linked to the human psyche. For thousands of years people lived in groups where everyone was equal and there was very little individuality. The appearance of the first mirrors in neolithic Turkey coincided with what archaeologists describe as the rise of a greater sense of individual self. Within a few centuries the first societies with rulers and slaves, rich and poor, appeared in nearby Mesopotamia. A similar shift seems to have occurred much more recently, when mirrors were introduced to highly traditional, isolated tribes in Papua New Guinea in the late 1960s. Within a very short time many of the tribes’ traditions and cultures had crumbled as people struggled with their new self-awareness.

Q. How did you come to select the eleven inventions within the book?

A. The most important question to me was what impact did the invention have on the human story? In the case of the 11 discussed in the book, it turned out to be quite a lot! So in the end the 11 selected themselves.

Q. Were there any other inventions that you would have included if space and time had permitted, and for what reasons?

A. I only briefly mention the microscope, because it was initially seen as a novelty device. It took 200 years for Louis Pasteur to develop his germ theory and make the link between microorganisms and disease.

Q. This is your first book. What were the main challenges you faced in writing it, and how did you overcome them?

A. I found all the research I did for the book so fascinating, I ended up going down lots of rabbit holes. That’s just a matter of pulling yourself out again and getting back on topic. Then trimming down all that research, losing tons of interesting stuff, was heart-breaking. But like they say, you’ve got to ‘kill your babies’ to write a book.

Q. What, to you, is key to making an ‘ideas’ book like yours engaging with readers?

A. It needs to leave space to let the readers do some of the work, so that they have their own ‘aha’ moments, just like in a thriller. Readers are smart; they want to go on a journey with the writer, not just be told stuff.

Q. What do you hope readers will come away with after reading A History of Seeing in Eleven Inventions?

A. A new awareness of and appreciation for all their senses, and how they affect not just our immediate experience but every aspect of our lives.

Q. Your book includes a postscript concerning Covid-19. Why did you think it important to include this?

A. Covid has had such a profound impact on all our senses that I felt I needed to address it. Both literally, in terms of the loss of smell and taste the disease can cause, and more generally in terms of all the restrictions on direct contact with one another, and how it has accelerated the trend towards a screen-based society that I discuss in the final chapters of the book.

Q. Now that the book is out, what are your plans as an author moving forward?

A. I’m researching another ‘ideas’ book in a completely different field. I’m really excited about its potential, but it has a way to go yet.